Online health communities, where patients with the same condition share experiences and advice, are generally interpreted by researchers as a positive outcome of the ‘online global village’ (Stadtelmann, Woratschek & Diederich, 2019).

My experience with these groups was not as the academics presented. I quit them soon after joining — and I don’t regret it.

The Diagnosis

Late last year, an appointment with a scoliosis clinic delivered some unexpected news to our family.

“Your daughter’s x-rays indicate Scheuermann’s Disease.”

We drove away from the appointment, trying to remember everything the doctor had said.

“It’s a rare condition…a spinal deformity…spinal brace 22 hours a day for two years and if that fails, a spine operation — which you want to avoid.”

Given the remembered snippets, I did what any modern-day mum would do — I went straight to Dr Google and read all I could on the condition.

Some of it was useful, but it lacked something — the personal experience of other people with the condition, or other parents who had children with the condition.

The ‘Family Stigma’

One of my first instincts after the initial appointment had been to post something on my Facebook page but I stopped myself as I knew this would be, as referred to by social media researchers, as an ‘intimate transgression of private information’ (Smith & Watson, 2013). My teenage daughter would not want this information shared in this forum — even if I would get positive reinforcement in the empathy it would elicit from others.

Also, the news of something happening to my child didn’t fit with my curated Facebook profile which documents and archives happy family moments; milestones, holidays and outings. Bad medical news would not fit there.

My instincts were right. Social media researchers have reported a ‘ family stigma’ in talking about a child’s disability or illness on social media (Ammari, Schoenebeck, and Morri, 2014).

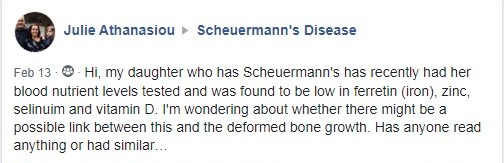

When I had exhausted the medical-centred explanations and with a self-imposed ban on my family-centred Facebook page, I instead joined several private Facebook pages set up by people who had the condition. My main aim was to learn from others how my daughter could manage to wear the prescribed brace.

The Scheuermann’s Disease-related Facebook sites’ privacy settings allowed for activities I wouldn’t do normally — I could ask questions, get real-life answers and be empathised with and give empathy to others without infringing on family and friends whose sympathy would feel too personal (Brady, Zhong, Morris and Bigham, 2013).

By splitting my Facebook presence between the public and the private, I could present myself as the mother of a child with a rare condition and ask questions to the people to whom it was relevant without attaching the ‘disease stigma’ to my public profile.

From Service Beneficiary to Service Provider

Initially, involvement in the groups was useful. I was what would be described by Stadtelmann et al. as a ‘service beneficiary’. I asked questions and the very helpful group members supplied useful answers (Stadtelmann, Woratschek and Diederich 2019) .

After learning more about the condition through my daughter’s experience, I found myself moving into an alternate role of the ‘service provider’. In this role, I was able to provide advice to others on practical subjects to manage the brace-wearing like the best mattress, the best undershirt, the best exercises, and so forth.

I also found myself in the role of the ‘empathiser’ providing kind words and helpful advice to new group members. In a time of powerlessness, when I couldn’t control my own child’s health, I found strength and purpose in helping others.

However, the positives of private groups comes at a price — a deluge of the negative experiences from people who feel they have no where else to vent.

Logging off private going public

Overtime, membership to the group was not worth the daily feed of sadness.

In contrast to the academic studies on the positive nature of these communities to empower patients, I found the primary users tend to be the worst-case scenarios.

Each day there were multiple posts from members who wanted to know which oxy-type drug others used for pain or pleas for help with suicidal thoughts. The failings of the health care system forced them to reach out to the online world as they were not receiving the support and care they needed in real life.

Recently, and in contrast, I also started to notice that the public Twitter hashtags relating to the condition are different — positive stories of hope for those living with the condition. There were other ways to present the story.

Although my role as ‘expert’ and ‘empathiser’ in the private Facebook groups felt useful, I could no longer align my online presence with the actual real-life experience. With the initial diagnosis-crisis over, my daughter’s life wasn’t like the people posting about drug-recommendations and suicidal ideation.

My adaptable, forward-thinking daughter was out living her life; wearing her brace, excelling at school, hanging with friends and most importantly looking forward to the future. I checked out of the private online health groups and decided I’d follow her example instead.

Cover image: ‘Living Life Offline’ by Stacey Nikolitsis © (All Rights Reserved)

References:

Ammari, T, Schoenebeck, S, Ringel Morris, M (2014), Accessing Social Support and Overcoming Judgment on Social Media among Parents of Children with Special Needs, Preceedings of theEighth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, University of Michigan Available at: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/ammari_ICWSM2014.pdf

Brady, E.L., Zhong, Y., Morris, M.R., and Bigham, J.P. (2013) Investigating the appropriateness of social network question asking as a resource for blind users. In Proc. CSCW 2013, ACM Press, 1225-1236. Available at: https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~jbigham/pubs/pdfs/2013/socialnetworkappropriateness.pdf